U.S. Army Lt. Col. Isaac Reeve Reports on the Surrender of His Command After the Secession of Texas

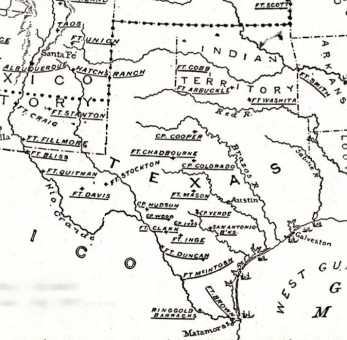

After the State of Texas adapted an ordinance of secession from the United States on February 1st, 1861, U.S. Army soldiers and cavalrymen at the various forts and garrisons scattered throughout the Lone Star State suddenly found

themselves in hostile territory. Then on February 18th, General David E. Twiggs, the commanding officer of the Department of Texas surrendered all U.S. military posts in his department to Texas authorities. Twiggs, a native of Georgia, would be vilified for his surrender, but he was in a difficult position. Armed secessionists were in the process of seizing U.S. government property at Twiggs’ headquarters in San Antonio when they surrounded him and demanded the surrender. Most of the U.S. troops in Texas–about 2300 total–were at 19 distant, widely dispersed posts without any means of quickly concentrating into an effective force. Twiggs would be dismissed from the U.S. Army on March 1st, 1861 and would briefly serve as a Confederate general in an administrative post early in the war before dying in 1862.

Twiggs negotiated an agreement where the military posts would be turned over to Texas, and the U.S. troops would be allowed to march to the Gulf Coast and leave for the north via ships. Some of these posts were a great distance from the coast, so the march would be lengthy both in miles and in the time it would take.

The longest march would be from Fort Bliss, then and now located at El Paso in West Texas. It was a nearly 700 mile march to Corpus Christi, and nearly 800 to Galveston from Fort Bliss. This march would be led by Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Van Duzen Reeve of the 8th U.S. Infantry. On March 31st, Reeve led his command (six companies of the 8th U.S. Infantry) out of Fort Bliss, bound for the Gulf Coast via San Antonio. His column was soon joined by the soldiers from two other far West Texas garrisons, Forts Quitman and Davis. After the initial shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12th, Confederate authorities revoked the Twiggs agreement to allow Federal soldiers safe passage north. Those who had not left Texas were to made prisoners of war.

Reeve’s column did not reach the San Antonio area until early May, weeks after the Twiggs agreement had been revoked. On May 9th, Reeve surrendered his command to superior Confederate forces at San Lucas Spring, 15 miles west of San Antonio. He filed these reports regarding the march and his reasons for surrendering:

CAMP NEAR SAN ANTONIO, TEX.,

May 12, 1861.SIR: I take the earliest opportunity possible to inform you that the six companies of the Eighth Infantry under my command, while marching for the coast under the agreement made between General Twiggs (late of the U.S. Army) and the State of Texas, to the effect that the troops should leave the State, were met by a force under command of Col. Earl Van Dorn, of the Southern Confederacy, and made prisoners of war. This occurred on the 9th instant, at San Lucas Spring, fifteen miles west of San Antonio. The force under my command, comprising the garrisons of Forts Bliss, Quitman, and Davis, amounted to an aggregate, when leaving the latter post, of 320. This embraces ten officers, two hospital stewards, and twelve musicians. Colonel Bomford, Sixth Infantry, was also with the command. On the day of surrender my command numbered 270 bayonets, being thus reduced by sickness, desertions, and stragglers (some of whom have since joined) who remained at Castroville from drunkenness or other causes. The force opposed to me numbered, as (then variously estimated at from 1,500 to 1,700 men) since ascertained to be, was 1,370 aggregate, the total being 848 cavalry, 361 infantry, and 95 artillery, with six field pieces.

When the demand for a surrender was made, I was told that the force opposed to me was “overwhelming.” I had halted in a good position for defense, and could have been overpowered only by a greatly superior force; and as none such was before me, I declined to surrender without the presentation of such force. It was on the march, and soon came in sight, but I was not satisfied of its strength until an officer of my command was permitted to examine and report to me the character and probable number of the forces. Upon his report I deemed resistance utterly hopeless, and therefore surrendered. My command is now encamped near the head of the San Antonio River, awaiting the orders of President Davis, to whom a messenger has been dispatched by Colonel Van Dom. The officers on duty with the command were Captain Blake, Lieutenants Bliss, Lazelle, Peck, Frank, Van Horn, and W. G. Jones, Eighth Infantry; Lieutenant Freedley, Third Infantry, and Assistant Surgeon Peters, Medical Department. A more detailed report will be made as soon as practicable.

I am, sir, yours, respectfully,

I. V. D. REEVE,

Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel, U. S. Army, Commanding.Col. L. THOMAS,

Adjutant-General U.S. Army, Washington, D.C.CAMP NEAR SAN ANTONIO, TEX., May 12, 1861.

SIR: In connection with the report which I have this day forwarded, relating to the surrender of the battalion of the Eighth Infantry under my command to the forces of the Confederate States of America, near this place, I also present the following details of the latter part of the march, and the circumstances which determined that surrender.

This report was not transmitted with the other, as it is extremely uncertain whether any reports of an official character are permitted to pass through the post-office here or those elsewhere in the South.

On leaving Fort Bliss sufficient transportation could be procured to carry subsistence for only forty days, in which time it was expected the command would reach San Antonio, making some little allowance for detentions by the way.

At Forts Quitman and Davis stores were taken to last the commands from those posts to San Antonio, not being able to carry more with the transportation at hand. From Camp Hudson to Fort Clark persons were occasionally seen on the road who appeared to be watching our movements, but they said they belonged to rangers who had been on a scout. At Fort Clark, where I arrived on the 2d of May, I learned that the mails had been detained for several days to prevent me from receiving information. It was reported by a stage passenger that the officers at San Antonio had been made prisoners of war. On all these subjects there were contradictory reports, and no information could be obtained which would warrant any hostile act on my part. Such supplies as were called for were readily furnished, and offers of services were proffered by the commanding officer. This did not look much like hostility, nor did I really suspect any. The garrison had been reinforced (being about 200 men), the post fortified to some extent, guns loaded and matches lighted on our approach; yet there did not appear any hostile intent towards us, as the explanation for all this was, that they “had heard that I had orders to attack and take Fort Clark.”

From this point rumors daily reached me, but so indefinite and contradictory, as to afford no sure ground for hostile action on my part; and by taking such I could not know but I should be the first to break the treaty under which we were marching.

On reaching Uvalde on the 5th (near Fort Inge), I felt more apprehension of hostility, though rumors were still very contradictory. To attempt, from this point, to return to New Mexico for the purpose of saving the command, would have been impracticable, for I had but five days’ rations, and our transportation was too much broken down to make the march without corn (which could not be had), even if everything but subsistence and ammunition had been abandoned. Behind us was the mounted force at Fort Clark, and a large mounted force said to be at San Antonio, reported to be from 700 to 2,000. At this time the only other method of escape left was to cross the Rio Grande, this being easy of accomplishment, but of very doubtful propriety, particularly as it was yet uncertain whether we should not only break the treaty with Texas, but also compromise the United States with Mexico by crossing troops into her soil.

On the 6th, while continuing our march, we heard that those companies at the coast had been disarmed, and that in all probability we would be also on our arrival there; that there would be a force of from 2,000 to 6,000 men against us. We then had no course open to us but to proceed, and, unless overpowered by numbers, to endeavor to fight our way to the coast, with the hope that some way of escape would be opened to us. On the 7th we heard that there were not more than 700 men in San Antonio, and such a force I knew would not be able to overpower us; and still with strong hope that we might be able to advance successfully, I purchased (on the 8th) at Castroville a small additional supply of subsistence stores (all I could), enough for two days, which included the 12th instant, but could have been made to last several days, had I a reasonable prospect of seizing more in San Antonio. Before reaching Castroville I learned that there were troops encamped on the west side of the Leon, seven miles from San Antonio; that there were cavalry, infantry, and artillery, with four guns. I encamped on the 8th on the east side of the Medina, opposite to Castroville. Late that evening I heard that the enemy would march to surround us in our camp, and I had before heard that a section of artillery was on the way down from Fort Clark, following on our rear; and there was further report that it would pass us that night on the way to San Antonio. To avoid surprise and be in possession of plenty of water, I marched that night at 12 o’clock to reach the Lioncito, six miles east of the Medina, and on my arrival there, finding no signs of the advance of the enemy, I marched on three miles farther to a point suggested and brought to my memory by Lieut. Z. R. Bliss, Eighth Infantry, called San Lucas Spring. There is quite a high hill a few hundred yards from the spring, having some houses, corrals, &c., which, together with the commanding position and a well of water in the yard, rendered this point a very strong one for a small command. This place is known as Allen’s Hill. It is eight miles from where the enemy was encamped, and there I made a halt to await his advance, and parked the wagon train for defense; all of which preparations were made a little after sunrise on the 9th.

About 9 o’clock two officers approached, bearing a white flag and a message from Colonel Van Dorn, demanding an unconditional surrender of the United States troops under my command, stating that he had an “overwhelming force.” I declined to surrender without the presentation of such a force or a report of an officer, whom I would select from my command, of its character and capacity of compelling a surrender. The advance of the enemy came in sight over a rise of ground about a mile distant, and as the whole force soon came in sight and continued in march down the long slope, Colonel Van Dorn’s messenger returned to me with directions to say that “if that display of force was not sufficient I could send an officer to examine it.” I replied that it was “not sufficient.” I directed Lieutenant Bliss to proceed, conducted by the same messenger, to make a careful examination of the enemy. He was taken to a point so distant that nothing satisfactory could be ascertained, and he informed his conductors that he would “make no report upon such an examination.” This being reported to Colonel Van Dorn, he permitted as close an examination as Lieutenant Bliss desired. The enemy had formed line on the low ground some half-mile in front of my position, perpendicular to and crossing the road, and neither force could be plainly seen by the other in consequence of the high bushes which intervened. Lieutenant Bliss rode the whole length of the enemy’s line within thirty yards, estimating the numbers and examining the character of his armament. He reported to me that the cavalry were armed with rifles and revolvers; the infantry with muskets (some rifle) and revolvers; that there were four pieces of artillery, with from ten to twelve men each; that he estimated the force at 1,200 at least, and there might be 1,500 (since ascertained to be 1,400). With this force before me, an odds of about five to one, being short of provisions, having no hope of re-enforcements, no means of leaving the coast, even should any portion of the command succeed in reaching it, and with every probability of utter annihilation in making the attempt, without any prospect of good to be attained, I deemed that stubborn resistance and consequent bloodshed and sacrifice of life would be inexcusable and criminal, and I therefore surrendered.

Colonel Van Dorn immediately withdrew his force, and permitted us to march to San Antonio with our arms and at our leisure. We arrived there on the 10th, and on the 11th an officer was sent to our camp to receive our arms and other public property, all of which was surrendered.

I will state here that we have been treated, in the circumstances of our capture, with generosity and delicacy, and harrowed and wounded as our feelings are, we have not had to bear personal contumely and insult.

I am, sir, yours, respectfully,

L V. D. REEVE,

Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel, U. S. Army, Commanding.Col. L. THOMAS,

Adjutant-General U. S. Army, Washington, D.C.KANKAKEE CITY, ILL., June 18, 1861.

SIR: I have the honor to report my arrival at this place yesterday, the 17th instant, having come from San Antonio, Tex., with as much dispatch as the means of travel and communication would permit, leaving that place on the 4th.

I inclose herewith a copy of my report made under date of May 12, fearing that that report did not reach your office in consequence of the disturbed state of the country and the uncertainty of the mails. I also inclose a detailed report of the latter portion of the march and surrender, to which reference was made in my former report. This latter report could have been long ago made had there been any reasonable prospect of its reaching you. This is the first point, where I have been able to stop, from which letters could be forwarded with safety.

I hereby report further how I happen to be here. After surrender the troops were paroled–the officers to the limits of the Confederate States of America, and the men placed under oath not to leave the county of Bexar, Texas. Up to the 4th of June Colonel Van Dorn was expecting orders to grant unlimited paroles to the officers, and told me that he had no doubt such would be granted on return of his messenger from Montgomery. The 1st instant I received the sad, crushing intelligence of the death of my oldest daughter, and Colonel Van Dorn at once offered me the privilege of coming home. I availed myself of his generosity, both with the view to make arrangements for the care of my remaining children and to communicate with the War Department, in the hope of being of some service to the prisoners of war in Texas by representing their true state and condition, Not knowing whether my reporting in person would be either desirable or proper, I send the following brief statement:

Up to the time I left San Antonio the troops were in quarters, and under the care and control of their own officers. They were allowed the usual subsistence and all the clothing necessary; had no restrictions as to limits, except attendance on retreat roll-call, and could be permitted to go anywhere within the county upon a written pass signed by their own officers. With the exception of some five or six they remained faithful to their Government, and refused all offers and inducements to join the Confederate service. The day before I left Colonel Van Dorn informed me that they would be moved into camp some five miles from town, and placed under charge of Confederate officers, who would attend to their wants, thus separating them from the care of their own officers. In all this they have been as well if not much better treated than is the usual fate of prisoners of war. Their peril consists in the fact that they are retained as hostages against the rigorous treatment of any prisoners who may fall into the power of the United States. Colonel Van Dorn does not regard the parole which is given to the officers as revocable by his Government, and their peril is not, therefore, the same as that of the men in his view of the case; therefore it is not easy to see, in the same view of the case, any good reasons for restrictions as to limits being made in the parole. The officers are furnished with quarters and board at the expense of the Confederacy, at least while they remain in San Antonio.

I shall be in Dansville, in New York, in a few days, where communications will reach me. Hoping that I may be justified in the course I have pursued, as represented in my reports,

I remain, sir, yours, very respectfully,

I. V. D. REEVE,

Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel, U.S. Army.Col. L. THOMAS,

Adjutant-General U. S. Army, Washington, D. C.

The captured men of the 8th Infantry were eventually released, and along with some new recruits, the companies of the unit reformed during 1862 and 1863 and served in the eastern theatre of operations for the rest of the war.

Sources:

Against the Grain: Colonel Henry M. Lazelle and the U.S. Army

by James Carson

Blood and Treasure: Confederate Empire in the Southwest by Donald S. Frazier

Compendium of the War of the Rebellion by Frederick Dyer

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume 1, Chapter VII.

Recollections of the Twiggs Surrender by Caroline Baldwin Darrow. In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume I. Edited by Clarence C. Buel and Robert U Underwood.

Amazon affiliate links: We may earn a small commission from purchases made from Amazon.com links at no cost to our visitors. For more info, please read our affiliate disclosure.

Thank you so much for this. My great-great-grandfather, Bernard Rowe, from County Meath, Ireland, was one of the Union soldiers in Company B. I knew the general facts about this surrender, which I’d gotten from pension records in the U.S. Archives, but had no idea of the details.

Sincerely yours,

J. Reek

Glad I could shed some light on this for you and thanks for visiting!