William T. Sherman’s Report on the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou

Before General Ulysses S. Grant’s launched his successful April to July 1863 campaign to take Vicksburg, Mississippi, he made several other attempts to take that important city on the Mississippi River. One of these involved two separate Union armies, one under his command and one under Major General William T. Sherman, attacking the city from two different directions.

In November 1862, Grant and 40,000 men began a movement south from Tennessee into northern Mississippi. His plan was to march along the line of the Mississippi Central Railroad and eventually attack Vicksburg from the east, with the railroad being his supply line. As Grant moved south, he hoped to draw the main Confederate army out of Vicksburg and into battle, while Sherman took four divisions down the Mississippi River and attacked the northern end of the city, which would be lightly defended if the main Rebel force was engaging Grant.

Grant advanced at a slow pace, repairing railroad bridges and establishing supply bases as he went. On December 20th, her ordered Sherman to proceed downriver. That same day, Confederate cavalry under Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked Union rail lines in Tennessee, while Major General Earl Van Dorn’s cavalry destroyed a major Federal supply depot at Holly Springs, Mississippi. With his supply lines in disrupted and his main supply base in the field destroyed, Grant decided to withdraw and regroup. He tried to inform Sherman, but the telegraph lines had been cut. With no orders to stop, Sherman continued.

With the Sherman’s force approaching the northern edge of Vicksburg, the Confederate defenders moved as many troops as possible to the high ground north of town known as the Walnut Hills, and hastily dug in and built a solid defensive position. When Grant began his withdrawal, more men were sent to the Walnut Hills, and about 19,000 well entrenched Confederates on high ground were waiting for Sherman

Sherman’s divisions arrived at the mouth of the Yazoo River, which emptied into the Mississippi slightly above and to the northwest of Vicksburg, on December 26th, 1862. The Yazoo ran roughly parallel to the Walnut Hills, and Chickasaw Bayou branched off the Yazoo and toward the Walnut Hills. The river was high and flooded the area, leaving little dry ground suitable for an army. The men would have to advance along narrow causeways or wade through tangled swampland in sight of Confederate artillery and infantry in order to attack, and would have to charge uphill to assault the entrenched enemy.

The Federals moved into position on the 27th and 28th, skirmishing with Rebel defenders. On the 29th, Sherman launched a full scale assault on the Confederate lines, which was repulsed with heavy Union casualties. Realizing the strong defensive position of the enemy, Sherman did not attack again, and after considering other options, withdrew to the mouth of the Yazoo on January 2nd, 1863.

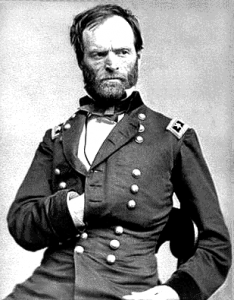

Sherman filed this report on the campaign:

HDQRS. RIGHT WING, ARMY OF THE TENNESSEE,

Camp, Milliken’s Bend, La., January 3, 1863.

SIR: I have heretofore reported my progress and the organization of the forces placed under my command up to the date of their embarkation at Memphis, on December 20, 1862. This was two days later than fixed by your instructions, but was as soon as transports could possibly reach us from Cairo and Saint Louis.On the 20th I proceeded to Helena and there met General Gorman, commanding officer, and arranged with him for the establishment at Friar’s Point of an regiment of infantry and a section of artillery, and a cavalry force of 2,000 men, under General Washburn, to operate from Friar’s Point over to the Tallahatchie, and if possible to communicate with General Grant.? also met General Frederick Steele, who was assigned to command the forces detailed to join me at that place. All of these were embarked on the 21st, and by my orders were rendezvoused at Friar’s Point. My whole force there being assembled we proceeded in order, led by Admiral Porter in his flag-boat Black Hawk, to Gaines’ Landing, and next day to Milliken’s Bend.

From that point I dispatched Burbridge’s brigade, of the First Division [A. J. Smith’s), to destroy a large section of the Vicksburg and Shreveport Railroad, near the Tensas River. This duty was admirably performed the roadway destroyed for many miles and several 1ong pieces of bridge and trestle work burned. General Burbridge found a great deal of cotton, corn, and cloth, the property of the Confederate Government, which he burned. Cotton, the property of private individuals, was left undisturbed. For a more particular account of the expedition I refer you to General Burbridge’s report herewith inclosed.

On December 25, without waiting for the return of Burbridge, I left General A. J. Smith, with the remainder of his division, to follow as soon as that detachment came in. With the other three divisions I proceeded opposite the mouth of the Yazoo, landing on the west bank of the Mississippi, whence I dispatched General Morgan L. Smith, with one of his brigades, to destroy another section of the same road at a point nearer Vicksburg. This work of destruction was also accomplished fully, so that the Vicksburg and Shreveport Railroad, by which vast amounts of supplies reach Vicksburg, is, and must remain for months, useless to our enemy.

On December 25, according to my promise made to General Grant, I had my force at the mouth of the Yazoo. The whole naval squadron of the Mississippi, iron-clads and wooden boats, were also there, Admiral D. D. Porter in command. Conferring with him, and with all positive information gained from every available source, we determined that the best point of debarkation was at a point on the Yazoo, 12 miles up, on an island formed by the Yazoo and Mississippi Rivers and a system of bayous or old channels.

On the 26th all the fleet proceeded in order up the Yazoo, gunboats leading and distributed along the column of transports to cover them against sharpshooters from this jungle and canebrake that cover the low banks of the Yazoo. In the fleet of transports Morgan’s division led, followed by Steele, he by Morgan L. Smith, and A. J. Smith brought up the rear. This latter division was delayed part of one day by the distance traveled by Burbridge’s brigade from Milliken’s Bend, and it did not come up until about noon of the 27th.

As soon as we reached the point of debarkation Do Courcy’s, Stuart’s and Blair’s brigades were sent forward in the direction of Vicksburg about 3 miles, and on the 27th the whole army was distributed and moved out in four columns: Steele’s above the month of Chickasaw Bayou; Morgan’s, with Blair’s brigade of Steele’s division, below the same bayou; Morgan L. Smith’s on the main road from Johnson’s plantation to Vicksburg, with orders to bear to his left, so as to strike the bayou about a mile south of where Morgan was ordered to cross it, and A. J. Smith’s division keeping on the main road.

All the heads of columns met the enemy’s pickets and drove them toward Vicksburg. During the night of the 27th the ground was reconnoitered as well as possible, and it was found to be as difficult as it could possibly be from nature and art. Immediately in our front was a bayou passable only at two points–on a narrow levee and on a sand bar which was perfectly commanded by the enemy’s sharpshooters that line the levee or parapet on its opposite bank. Behind this was an irregular strip of bench or table land, on which was constructed a series of rifle-pits and batteries, and behind that a high, abrupt range of hills, whose scarred sides were marked all the way up with rifle-trenches, and the crowns of the principal hills presented heavy batteries.

The county road leading from Vicksburg to Yazoo City was along the foot of these hills, and answered an admirable purpose to the enemy as a covered way along which he moved his artillery and infantry promptly to meet us at any point at which we attempted to cross this difficult bayou. Nevertheless, that bayou with its levee parapet, backed by the lines of rifle pits, batteries, and frowning hill, had to be passed before we could reach terra firma and meet our enemy on anything like fair terms.

Steele in his progress followed substantially an old levee back from the Yazoo to the foot of the hills north of Thompson’s Lake, but found that in order to reach the hard land he would have to cross a long corduroy causeway with a battery enfilading it, others cross-firing it, with a similar line of rifle-pits and trenches before described. He skirmished with the enemy on the morning of the 28th, while the other columns were similarly engaged; but on a close and critical examination of the swamp and causeway in his front, with the batteries and rifle-pits well manned, he came to the conclusion that it was impossible for him to reach the county road without a fearful sacrifice. As soon as he reported this to me officially, and that he could not cross over from his position to the one occupied by our center, I ordered him to retract; his steps and cross back in steamboats to the southwest side of Chickasaw Bayou, and to support General Morgan’s division, which he accomplished during the night of the 28th, arriving in time to support him and take part in the assault of the 29th.

General Morgan’s division was evidently on the best of all existing roads from the Yazoo River to the firm land. He had attached to his train the pontoons with which to make a bridge in addition to the ford

or crossing which I knew was in his front–the same by which the enemy’s pickets had retreated. The pontoon bridge was placed dining the night across a bayou supposed to be the main bayou, but which turned out to be an inferior one, and it was therefore useless; but the natural crossing remained, and I ordered him to cross over with his division and carry the line of works to the summit of the hill by a determined assault.

During the early part of the day of the 28th a heavy fog enveloped the whole country, but General Morgan advanced De Conroy’s brigade and engaged the enemy; heavy firing of artillery and infantry were sustained, and his column moved on until he encountered the real bayou; this again checked his progress, and was not passed until the next day.

At the point; where Morgan L. Smith’s division reached the bayou was a narrow sand-spit, with abatis thrown down by the enemy on our side, with the same deep, boggy bayou, with its levee parapet and system of cross-batteries and rifle-pits on the other side. To pass it in his front by the flank would have been utter destruction, for the head of the column would have been swept away as fast as it presented itself above the steep bank. General Smith, while reconnoitering it early on the morning of the 28th, was, during the heavy fog, shot in the hip by a chance rifle-bullet, which disabled him, and lost to me one of my best and most daring leaders, and to the United States the service of a practical soldier and enthusiastic patriot. I cannot exaggerate the loss to me personally and officially of General Morgan L. Smith at that critical moment. His wound in the hip disabled him and he was sent to the boat. General D. Stuart succeeded to his place and to the execution of’ his orders. General Stuart studied the nature of the ground in his front and saw all its difficulties, but made the best possible disposition to pass over his division (the Second) whenever he heard General Morgan engaged on his left.

To his right General A. J. Smith had placed Burbridge’s brigade of his division next to Stuart, with orders to make rafts and cross over a portion of his men; to dispose his artillery so as to fire at the enemy across the bayou and produce the effect of a diversion. His other brigade (Landram’s) occupied key position on the main road, with pickets and supports pushed well forward into the tangled abatis within three-fourths of a mile of the enemy’s forts and in plain view of the city of Vicksburg.

Our boats still lay at our place of debarkation, covered by the gun-boats and by four regiments of infantry—one of each division. Such was the disposition of our forces during the night of the 27th [28th].

The enemy’s right was a series of batteries or forts 7 miles above us on the Yazoo, at the first bluff, near Snyder’s house, called Drumgould’s Bluff; his left, the fortified city of Vicksburg, and his line connecting these was near 14 miles in extent, and was a natural fortification strengthened by a year’s labor of thousands of negroes, directed by educated and skilled officers.

My plan was by a prompt and concentrated movement to break the center near Chickasaw Creek, at the head of a bayou of the same name, and once in position to turn to the right (Vicksburg) or left (Drumgould’s Bluff). According to information then obtained I supposed their organized forces to amount to about 15,000, which could be re-en-forced at the rate of about 4,000 a day, provided General Grant did not occupy all the attention of Pemberton’s threes at Grenada, or Rosecrans those of Bragg in Tennessee.

Not one word could I hear from General Grant, who was supposed to be pushing south, or of General Banks, supposed to be ascending the Mississippi. Time being everything to us, I determined to assault the hills in front of Morgan on the morning of the 29th–Morgan’s division to carry the position to the summit of the hill; Steele’s division to sup port him and hold the county road. I had placed General A. J. Smith in command of his own division(First) and that of M. L. Smith (Second), with orders to cross on the sand-spit, undermine the steep bank of the bayou on the farther side, and carry at all events the levee parapet and first line of rifle-pits, to prevent a concentration on Morgan.

It was near 12 m. when Morgan was ready, by which time Baler’s and There’s brigades, of Steele’s division, were up to him and took part in the assault; and Hovel’s brigade was close at hand. All the troops were massed as close as possible, and all our supports were well in hand.

The assault was made and a lodgment effected on the hard table-land near the county road, and the head of the assaulting columns reached different points of the enemy’s works, but there met so withering a fire from the rifle-pits and cross-fire of grape and canister from the batteries that the column faltered, and finally fell back to the point of starting, leaving many dead, wounded, and prisoners in the hands of the enemy. For a more perfect understanding of this short and desperate struggle I refer to the reports of Generals Morgan, Blair, Steele, and others, inclosed.

General Morgan’s first report to me was that the troops were not discouraged at all, though the losses in Baler’s and De Course’s brigades were heavy, and he would renew the assault in half an hour; but the assault was not again attempted.

I urged General A. J. Smith to push his attack, though it had to be made across a narrow sand bar and up a narrow path, in the nature of a breach, as a diversion in favor of Morgan, or real attack, according to its success.

During Morgan’s progress he passed over the Sixth Missouri under circumstances that called for all the individual courage for which that admirable regiment is justly famous. Its crossing was covered by the Thirteenth U.S. Regulars, deployed as skirmishers up to the near bank of the bayou, covered as well as possible by fallen trees, and firing at any of the enemy’s sharpshooters that showed a mark above the levee. Before this crossing all the ground opposite was completely swept by our artillery, under the immediate supervision of Major Taylor, chief of artillery. The Sixth Missouri crossed over rapidly by companies, and lay under the bank of the bayou, with the enemy’s sharpshooters over their heads within a few feet—so near that these sharpshooters held out their muskets and fired down vertically upon our men. The orders were to undermine this bank and make a road up it, but it was impossible; and after the repulse of Morgan’s assault I ordered General A. J. Smith to retire this regiment under cover of darkness, which was successfully done. Their loss was heavy, but I leave to the brigade and division commanders to give names and exact figures. While this was going on Burbridge was skirmishing across the bayou at his front, and Landram pushed his advance, through the close abatis or entanglement of fallen timber, close up to Vicksburg. When the night of the 29th closed in we stood upon our original ground and had suffered a repulse. The effort was necessary to a successful accomplishment of my orders, and the combinations were the best possible under the circumstances. I assume all the responsibility and attach fault to no one, and am generally satisfied with the high spirit manifested by all.

During this night it rained very hard, and our men were exposed to it in the miry, swampy ground, sheltered only by their blankets and rubber shawls ; but during the following day it cleared off warm.

During the night of the 29th I visited Admiral Porter on his flag-boat and advised him of the exact condition of affairs, and on the following day, after a personal examination of the various positions, I was forced to the conclusion that we could not break the enemy’s center without being too crippled to act with any vigor afterward.

New combinations therefore became necessary. I proposed to Admiral Porter if he would cover a landing at some high point close up to the Drumgould batteries I would hold the present ground and send 10,000 choice troops and assault the batteries there–that is, attack the enemy’s right–which, if successful, would give us the substantial possession of the Yazoo River and place us in connection with General Grant.

Admiral Porter promptly and heartily agreed; and on a full conference, after close questioning some negroes as to the nature of the ground about the mouth of the Skillet Goliah, we came to the conclusion that no road or firm ground could be found south of that bayou. It was therefore agreed that the 10,000 should be embarked immediately after dark during the night of December 31, and under cover of all the gun-boats proceed before day slowly and silently up to the batteries above and engage them, the gunboats to silence the batteries, the troops then to disembark, storm the batteries, and hold them. While this was going on I was to attack the enemy here and hold him in check, preventing re-enforcements going up to the bluff, and in case of success to move all my forces to that point. Steele’s division and the First Brigade of my Second Division were designated and embarked; the gunboats were all in position and up to midnight everything appeared favorable.

I left the admiral about 12 o’clock at night and the assault was to take place about 4 a.m. I went to my camp and had all the officers at their posts ready to act on the first sound of cannonading in the direction of Drumgould’s Bluff; but about daylight I received a note from General Steele stating that the admiral had found the fog so dense on the river that the boats could not move, and that the expedition must be deferred to another night; but before the night of January 1, 1863, I received a note from Admiral Porter that “inasmuch as the moon does not set to-night until 5.25 the landing must be a daylight affair, which, in my (his) opinion, is too hazardous to try.”

Of course I was sadly disappointed, as it was the only remaining chance of our securing a lodgment on the ridge between the Yazoo and Black Rivers from which to operate against Vicksburg and the railroad east, as also to secure the navigation of the Yazoo River, but I am forced to admit the admiral’s judgment was well founded, and that even in case of success the assault on the batteries of Drumgould’s Bluff would have been attended with a fearful sacrifice of life.

One-third of my command had a already embarked for the expedition; the rest were bivouacked in low, swampy, timbered ground, which a single night’s rain would have made a quagmire, if not a lake. Marks of overflow stained the trees 10 and 12 feet above their roots, and as further attempts against the center were deemed by all the brigade and division commanders as impracticable, I saw no good reason for remaining in so unenviable a place any longer. All the necessary orders were made and all the men and materials were re-embarked on the original transports by sunrise of January 2.

During all this time the enemy displayed in our front, whenever we presented ourselves, large masses of infantry and cavalry; artillery crowned the summits of the hills, appeared in the batteries on their faces, and field-guns presented themselves everywhere along the county road. We could hear their cars coming and departing all the time, and large re-enforcements were doubtless arriving, and as the rumor of General Grant having fallen behind the Tallahatchie became confirmed by my receiving no intelligence from him, I was forced to the conclusion that it was not only prudent but proper that I should move my command to some other point. Two suggested themselves–the Louisiana shore opposite the mouth of the Yazoo, and Milliken’s Bend. The latter had many advantages, large extent of cleared land, some houses for storage, better roads back, a better chance for corn and forage, with all the same advantages for operating against the enemy inland on the river below Vicksburg or at any point above where he might attempt to interrupt the navigation of the Mississippi. My mind had settled down on this point when, all my troops being on board their transports ready to move, on the morning of January 2 I learned from Admiral Porter that General McClernand had arrived at the mouth of the Yazoo. Fearing that any premature move on my part might compromise his plans for the future I determined to remain where we were until I consulted him, which I did in person, and with his approval I then proceeded to carry out my previous determination to land my command at Milliken’s Bend and dispatch back to the North the fleet of transport’s which had carried them. This has been so far accomplished that my entire command is now at Milliken’s Bend.

The naval squadron, Admiral Porter, now holds command of the Mississippi to Vicksburg and the Yazoo up to Drumgould’s Bluff, both of which points must in time be reduced to our possession; but it is for other minds than mine to devise the way.

The officers and men composing my command are in good spirits disappointed, of course, at our want of success, but by no means discouraged.

We re-embarked our whole command in the sight of the enemy’s batteries and army unopposed, remaining in full view the whole day, and then deliberately moved to Milliken’s Bend.I attribute our failure to the strength of the enemy’s position, both natural and artificial, and not to his superior fighting; but as we must all in the future have ample opportunities to test this quality it is foolish to discuss it.

I will transmit with this detailed reports of division and brigade commanders, with a statement of killed, wounded, and prisoners, and names as far as can be obtained. The only real fighting was during the assault by Morgan’s and Steele’s divisions and at the time of crossing the Sixth Missouri, during the afternoon of December 29, by the Second Division.

Picket skirmishing and rifle practice across Chickasaw Bayou was constant for four days. This cost us the lives of several valuable officers and men and many wounded. All our wounded were promptly removed to the steamers selected as hospital boats where they have received the best possible care.

I also inclose a map made by Lieutenants Pitzman and Frick, giving all our positions during the period embraced in this report.

I have the honor to be, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

Col. JOHN A. RAWLINS,

Assistant Adjutant-General to General Grant,

Oxford, Miss.: at last reliable accounts.

In the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, also referred to as the Battle of Chickasaw Bluffs, total Union casualties were 208 killed, 1005 wounded, and 563 captured or missing, while the Confederates had 63 killed, 134 wounded, and 10 missing or captured.

Sources:

“The Assault on Chickasaw Bluffs” by George W. Morgan. In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III, edited by Robert U. Johnson and Clarence C. Buel.

The Guide to the Vicksburg Campaign (U.S. Army War College Guides to Civil War Battles)

Edited by Leonard Fullenkamp, Stephen Bowman, and Jay Luvaas.

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I Volume XVII Part 1.

The Vicksburg Campaign, Volume I, by Edwin C. Bearss

Amazon affiliate links: We may earn a small commission from purchases made from Amazon.com links at no cost to our visitors. For more info, please read our affiliate disclosure.