Battle and Siege of Lexington Missouri 1861 Facts and Trivia

Date: September 18th-20th, 1861

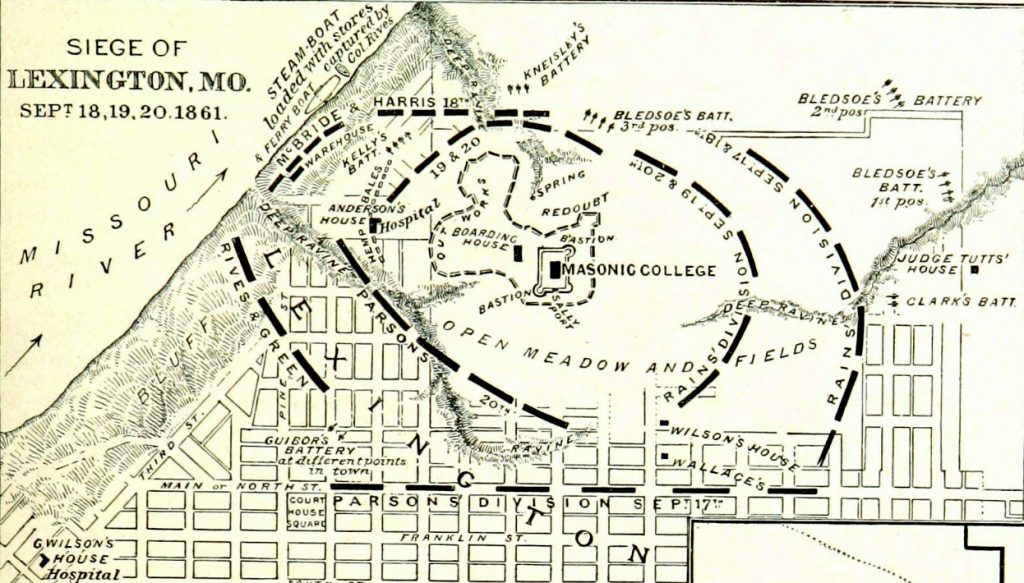

Location: Approximately 40 miles east of Kansas City, in Lafayette County, Missouri

Approximate Troop Strength: Union 3,500; Missouri State Guard (Confederate) 15,000.

Commanders: Colonel James Mulligan (Union), Major General Sterling Price (Missouri State Guard).

Estimated Union Casualties: 39 killed, 120 wounded, remainder captured.

Estimated Confederate Casualties: 30 killed, 120 wounded.

Result: Confederate victory

What Happened: Following the Confederate victory at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in southwest Missouri on August 10th, Price marched his army of approximately 7000 Missouri State Guardsmen north along the Missouri-Kansas border. On September 2nd, Price defeated a Union force from Fort Scott, Kansas at the Battle of Dry Wood Creek and continued north, arriving at Lexington on September 12th.

The Union forces at Lexington included the 1st Illinois Cavalry, the 13th Missouri Infantry, the pro Union Missouri Home Guard, the 23rd Illinois Infantry, a battalion of U.S. Reserves, and a detachment of the 27th Missouri Mounted Infantry. Colonel Mulligan of the 23rd Illinois Infantry was overall commander of the Union garrison. The Federals built entrenchments and fortifications on some open ground around the Masonic College building.

In addition to infantry and cavalry, both sides had artillery batteries that were heavily utilized in the fighting. One of the Missouri State Guard artillerists was Churchill Clark, grandson of William Clark, one of the explorers of the famous Lewis and Clark expedition.

Additional Missouri State Guard troops arrived over the next few days with the total reaching 15,000. On the 18th, State Guard troops surrounded the Union positions, cutting off all escape, including by riverboat on the nearby Missouri River. This also cut off a source of water for the Union defenders, and thirst became a factor as the water supply inside the garrison was depleted and both the river and some springs outside the Union fortifications became unreachable. Fighting began on the 18th and continued into the 20th, when Mulligan, realizing that the situation was hopeless and no reinforcements had arrived, surrendered.

Commanders

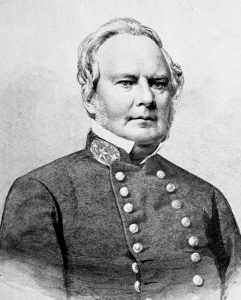

Major General Sterling Price fought at the Battles of Wilson’s Creek, Pea Ridge, and Helena in the Trans Mississippi theatre, as well as Iuka and Corinth in Mississippi. Following the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862, Price merged the Missouri State Guard into the regular Confederate Army. Price led an expedition in the summer and fall of 1964 to recapture Missouri, and after some initial success, he was defeated at the Battle of Westport. Price led his retreating troops south in western Missouri and eastern Kansas, where additional fighting with the pursuing Union forces occurred before his army eventually made it to Texas. Price survived the war.

Colonel James Mulligan, captured at Lexington, was eventually exchanged and returned to the 23rd Illinois. In 1862, his regiment was sent east and

would fight in Virginia and what would become the new state of West Virginia for the rest of the war. Mulligan would become a division commander and was mortally wounded at the Second Battle of Kernstown, Virginia, on July 24th, 1864.

Another Union regiment commander, Colonel Everett Peabody of the 13th Missouri Infantry, was a brigade commander at the Battle of Shiloh. He was killed in action there on April 6th, 1962.

Urban fighting

Civil War battles in rural area were much more common than fighting in towns, but the Battle of Lexington was an example of the latter. The Masonic College building was an important part of the Union fortifications, as well as the Union Headquarters, and drew a great deal of musket and artillery fire. Houses and businesses were damaged by artillery fire. Price set up his headquarters in a bank building. Some of the heaviest fighting took place at the Anderson House, a large private residence about a hundred yards west of the main Federal works which was used as a hospital for wounded Union troops at the outset of the fighting. It was a questionable decision to put a hospital in a building outside the main Union works in a strategic location, especially when the outnumbered Federals would be compelled to retire behind their inner fortifications. The Missouri State Guard took the Anderson House on the opening day of battle, and the Union counterattacked to try and retake it. Fighting floor to floor, the Federals briefly retook the building before the Missouri State Guard drove them out for good.

In 1896, Private (and later Captain) George H. Palmer of the 1st Illinois Cavalry was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in the counterattack on the Anderson House.

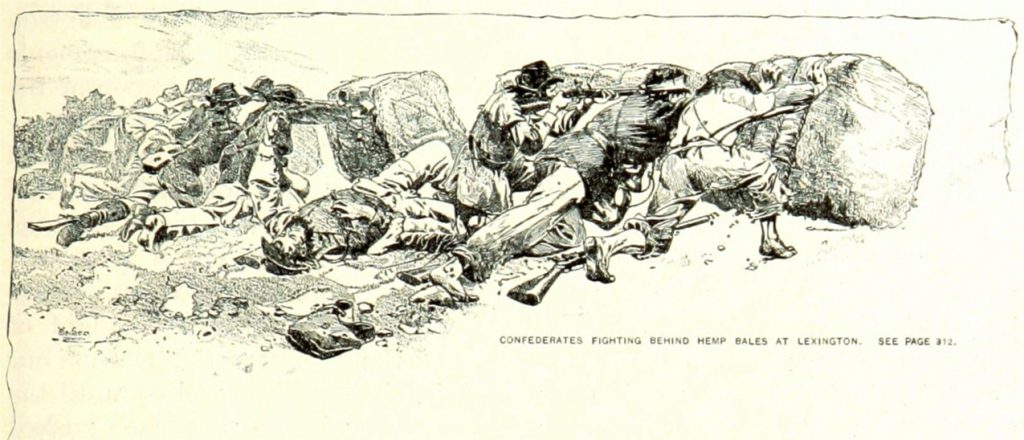

Battle of the Hemp Bales

On the final day of battle, Missouri State Guard troops began rolling large round bales of hemp from either side of the Anderson House towards the main Federal works. These bales had been wetted down with water from the river to prevent them from catching fire and served as mobile breastworks for the attackers. The tactic was effective, allowing the Missouri troops to close in on the Union works, and was one of the decisive factors in the defeat of the Federals. Because of this, the Battle of Lexington is also referred to as the Battle of the Hemp Bales. Other names for it are the Siege of Lexington and First Battle of Lexington.

Sources:

The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History by Louis S. Gerteis

A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion By Frederick H. Dyer

The Siege of Lexington, Mo. by James A. Mulligan. In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume I, edited by Robert U. Johnson and Clarence C. Buel

The Siege of Lexington Missouri: The Battle of the Hemp Bales by Larry Wood

Amazon affiliate links: We may earn a small commission from purchases made from Amazon.com links at no cost to our visitors. For more info, please read our affiliate disclosure.