Before She Became a Famous Novelist, Louisa May Alcott Served as a Nurse in the Civil War

When the Civil War began in 1861, Louisa May Alcott was an aspiring writer working for the Atlantic Monthly magazine, the forerunner of today’s Atlantic. Born in Pennsylvania in 1832, her family eventually moved to Massachusetts. Her father, Bronson, was an educator who knew many of the famous New England writers and intellectuals of the day, no doubt sparking some interest in writing in his daughter. Louisa began her professional writing career with poems and short stories, sometimes under pen names, in the 1850s. She began writing for the Atlantic Monthly in 1860.

The Alcotts were also abolitionists, and their home served as a station on the Underground Railroad, helping to clandestinely move fugitive slaves out of the U.S. to safety in Canada. This, along with Louisa’s feelings of patriotism, contributed to her desire to take an active role in the Civil War. In December of 1862, she signed up for a three month stint as a nurse in Union Hospital, a converted hotel, in Georgetown, D.C.

Alcott’s time as a nurse in the hospital began at about the time the Army of the Potomac suffered defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, at a cost of thousands of casualties. The hospital was soon overwhelmed with wounded soldiers, forcing the novice nurse to quickly learn how to take care of them. The hospital’s patients also included many ill soldiers, as diseases like dysentery and typhoid fever were rampant in both armies, taking more lives than were lost in battle. Alcott herself came down with typhoid fever, ending her term as a nurse after six weeks.

Louisa would frequently write letters home during her time at the hospital, describing everything she saw and experienced. After she returned home, she was encouraged to publish the letters. Though she was reluctant to do so, she finally did arrange them for publishing, renaming the central character and narrator as Tribulation Periwinkle instead of using her own name. These writings were published in the abolitionist magazine Boston Commonwealth in May and June of 1863, and were very well received. This raised Alcott’s profile in the literary world, and she was approached about publishing the writings in book form. She agreed, and he resulting volume was called Hospital Sketches.

Hospital Sketches was a critical and financial success for Alcott. Her literary career took off after that, and she became a successful novel and short story writer, with her most famous work being the novel Little Women, published in 1868.

Here are a couple of excerpts from Hospital Sketches. The first is Alcott’s reaction upon seeing the wounded from Fredericksburg for the first time:

There they were! “our brave boys,” as the papers justly call them, for cowards could hardly have been so riddled with shot and shell, so torn and shattered, nor have borne suffering for which we have no name, with an uncomplaining fortitude, which made one glad to cherish each like a brother. In they came, some on stretchers, some in men’s arms, some feebly staggering along propped on rude crutches, and one lay stark and still with covered face, as a comrade gave his name to be recorded before they carried him away to the dead house. All was hurry and confusion, the hall was full of these wrecks of humanity, for the most exhausted could not reach a bed till duly ticketed and registered; the walls were lined with rows of such as could sit, the floor covered with the more disabled, the steps and doorways filled with helpers and lookers on; the sound of many feet and voices made that usually quiet hour as noisy as noon; and, in the midst of it all, the matron’s motherly face brought more comfort to many a poor soul, than the cordial draughts she administered, or the cheery words that welcomed all, making of the hospital a home.

The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty…

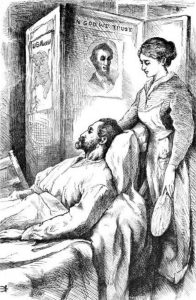

This passage is about a dying soldier named John who had been shot in the chest, with the ball breaking a rib and hitting his left lung.

I had been summoned to many death beds in my life, but to none that made my heart ache as it did then, since my mother called me to watch the departure of a spirit akin to this in its gentleness and patient strength. As I went in, John stretched out both hands:

“I knew you’d come! I guess I’m moving on, ma’am.”

He was; and so rapidly that even while he spoke, over his face I saw the grey veil falling that no human hand can lift. I sat down by him, wiped the drops from his forehead, stirred the air about him with the slow wave of a fan, and waited to help him die. He stood in sore need of help—and I could do so little, for, as the doctor had foretold, the strong body rebelled against death, and fought every inch of the way, forcing him to draw each breath with a spasm, and clench his hands with an imploring look, as if he asked, “How long must I endure this, and be still!” For hours he suffered dumbly, without a moment’s respite, or a moment’s murmuring; his limbs grew cold, his face damp, his lips white, and, again, he tore the covering off his breast, as if the lightest weight added to his agony; yet through it all, his eyes never lost their perfect serenity, and the man’s soul seemed to sit therein, undaunted by the ills that vexed his flesh…

…The first red streak of dawn was warming the grey east, a herald of the coming sun; John saw it, and with the love of light which lingers in us to the end, seemed to read in it a sign of hope of help, for, over his whole face there broke that mysterious expression, brighter than any smile, which often comes to eyes that look their last. He laid himself gently down; and, stretching out his strong right arm, as if to grasp and bring the blessed air to his lips in a fuller flow, lapsed into a merciful unconsciousness, which assured us that for him suffering was forever past. He died then; for, though the heavy breaths still tore their way up for a little longer, they were but the waves of an ebbing tide that beat unfelt against the wreck, which an immortal voyager had deserted with a smile.

Sources:

Hospital Sketches by Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott: Her Life, Letters, and Journals edited by Ednah D. Cheney

Women in the Civil War by Mary Elizabeth Massey

Amazon affiliate links: We may earn a small commission from purchases made from Amazon.com links at no cost to our visitors. For more info, please read our affiliate disclosure.